Women’s Role in Political and Social Life in Syria

Syrian women have been critical to societal and political changes within Syria, throughout the twentieth century until today, even if their role has been deemed limited. At the beginning of the twentieth century, educated and upper-class women founded a movement for women’s rights. The first women’s organization in Damascus, Light of Damascus or Noor al-Fayha, was founded by Nazik Al-Abid in 1919. In 1928, Lebanese-Syrian feminist Nazira Zain al-Din published a book criticizing the practice of concealing by the hijab, arguing that equality between women and men is required in Islam. Shortly after, the first Eastern Women Congress was hosted in Damascus in 1930. Another important figure in Syria's history is Thuraya Al-Hafez. She co-founded a newspaper called Barada in 1945, demanding political and social rights for women. In the 1950s, Hafez was the first woman to run for parliament in Syria, resulting in women holding four out of the available 173 seats by 1971. When the Baath Party took power in 1963, it supported women’s participation in society and equality between women and men. In 1967, a coalition of women's welfare societies, educational associations, and voluntary councils came together to form a General Union of Women. During the 1970s of the last century and on, women’s roles were very limited and linked to the Baath Party.

A significant figure in Syrian political life was Butaina Shaaban, a feminist writer, who published Both Left and Right Handed: Arab Women Talk About Their Lives in the United States in 1993. She served President Hafez al-Asad as a private translator in the 1990s and was appointed as Head of Press and Public Relation at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 2002, Prominent Spokesperson for Syria in 2003, and Minister of Expatriate Affairs by September of the same year. In 2016, Hadiya Khalaf Abbas led the Syrian Parliament as the first female speaker to hold that position.

Women’s role in Political and Social Life Pre-Civil War

Syrian women acquired the right to vote in 1949 and, subsequently, received universal suffrage in 1953. Despite their increasing access to higher education and employment, women remain under-represented in public and political life. In 2003, Syria endorsed the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), however, in 2007 the CEDAW Committee conveyed concerns about the ongoing low levels of women’s representation. No obvious change has been seen in time the Syrian government has promised to raise the representation of women in decision-making positions to 30. In 2005, the participation of women in the Syrian Parliament was only 12 percent and only 4.2 percent in local administrative councils.

The current Syrian law has many discriminatory sections against women. In 2007, the CEDAW Committee asked Syria to “give high priority to its law reform process and to modify or repeal . . . [such] discriminatory legislation, including discriminatory provisions in its Personal Status Act, Penal Code, and Nationality Act.” Currently, the General Women’s Union of Syria (GWU) is the only legal women’s organization operating in Syria, which was established by the government in 1967. The GWU is dominated by the ruling Ba’ath party; its officials are appointed and promoted from within the party hierarchy and receive financial support from the government. All other women’s groups operate illegally and are prohibited from receiving any funding even from abroad, due to local laws that prohibit donor grants from abroad.

Women’s Role During the Syrian Civil War

Since its beginning in March 2011, women have played a prominent role in the Syrian Uprising. Women were at the front lines of the uprising and participated in several movements, oftentimes risking their lives. Women always demanded democratic reforms, human rights, and to end the regime violence. In terms of military action, women joined several armed groups from the Kurdish and opposition forces. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights has reported that about 150 Kurdish women in Aleppo have set up the first female battalion, calling themselves the “Martyr Rokan Battalion.” Since they were not searched at checkpoints, women helped to transport weapons and supplies for opposition forces.

Even though the war in Syria has forced women to have a greater role in daily life by assuming more responsibilities, since the beginning of the conflict they have often felt the brunt of its effects. Based on a United Nations (UN) Women report, around 5.7 million refugees have fled the country since the conflict began in 2011, more than 50 percent of whom are women. According to United Nations Population Fund (NFPA) response report in March 2015, 3 million women have been affected by the crisis in Syria, 500,000 of whom were pregnant. Of the 3.9 million registered refugees, 1 million were women, and 70,000 were pregnant. Many women and girls were attacked in public or in their homes by Assad regime-affiliated armed men. These rapes sometimes occurred in front of family members. During ISIS’s control over some Syrian territories, women were forced to obey the Islamic Sharia law by requiring them to wear hijabs and full-length robes, known as abayas. Syrian security forces also targeted women and thousands of the women have survived torture and rape, while the jails have been filled with women.

Both the Syrian regime and extremist groups have restricted women’s rights for a long period of time. “Certain extremist armed opposition groups are imposing strict and discriminatory rules on women and girls that have no basis in Syrian law,” Human Rights Watch said. Restrictions on clothing, movement, employment, and education were imposed on hundreds of women in areas ruled by ISIS and Jabhat al-Nusra.

Women’s Current Role in Syria

The COVID-19 pandemic has had tremendous impacts on Syrian refugees, with refugees in host countries such as Lebanon having limited access to healthcare and medical supplies. Also, 62 percent of Syrian refugee women are working in the informal sector, mainly in agriculture. Within Syria, the pandemic’s economic impact has led to job losses for many. According to interviews with 69 women in Idlib and Aleppo, 71 percent of women were reported to feel unsafe and fear possible COVID-19 infection and displacement.

The war in Syria forced women to take on responsibilities previously reserved for men, for example, making hand-made carpets, fishing nets, and other manual labor. However, having such opportunities does not mean equality. On paper, women were granted the right to control their own property, business, and assets when Syria adopted its civil and commercial codes in 1948. In reality, social barriers have usually impeded women’s roles in terms of employment and work opportunities. A Jordanian non-profit organization carried out a survey of Syrian women in 2017 and noted that 81 percent of the interviewed women said that “the social norms in Syria truly impede women’s success.”

interviewed women said that “the social norms in Syria truly impede women’s success.” Since the beginning of the war, women started efforts to strengthen civil peace and bring peace to Syria through women's initiatives and organizations. With the beginning of displacement, women started initiatives aimed at helping displaced women in various regions. These initiatives expanded and became more organized with the exacerbation of displacement resulting in the emergence of specialized women's organizations and teams. Subsequently, efforts aimed at greater and broader representation of women in the political process increased, opening more space for women to build a peaceful future in Syria. Several initiatives emerged, such as:

ِWomen’s Advisory Committee: formed by the High Negotiations Committee participating in the negotiations for a political solution in Geneva, on February 2016, and was composed of 40 women, with the aim of achieving the effective participation of Syrian women, within the framework of the work of the High Negotiations Committee

The Women’s Advisory Council: the UN Special Envoy for Syria Staffan de Mistura announced the formation of the Women’s Advisory Council in February 2016, and its main task is to provide proposals and consultations to the UN envoy on the situation in Syria, and the legal, social and constitutional future visions for Syria.

The Syrian Feminist Political Movement: announced on October 4, 2017, the movement was announced at a founding conference held in Paris. It aims to present the active voice of Syrian women and set a future vision for Syria, through women’s real participation in the Syrian negotiations without being satisfied with the advisory role.

These initiatives point to women's participation in decision-making levels and the process of rebuilding and stabilizing Syria. This includes their participation in national, regional, and international institutions, conflict prevention mechanisms, peace negotiations, and peacekeeping operations.

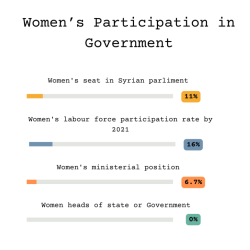

Women’s Participation in Government

Women seats in the Syrian Parliament: 28 out of 250 (11.2 percent)

Proportion of women seats in parliament (%)

Women seats in Labour Force by 2021: 16

Women Ministerial Positions: 2 out of 30 (6.7%)

No Women has been elected or appointed as head of state or government

Key Notable Women in Syria

Asma al-Assad, the First Lady of Syria and the wife of the current President Assad.

Hadiya Khalaf Abbas, Speaker of the People's Council of Syria (June 2016-July 2017).

Asya Abdullah, the co-chairwoman of the Democratic Union Party (PYD), the leading political party in Rojava.

Najah al-Attar, Vice President of Syria (since 2006).

Randa Kassis, President of The Astana Platform of the Syrian opposition.

Suheir Atassi, Vice President of the opposition government.

Rima al-Qadiri, a Syrian Arab politician and a Minister of Social Affairs and Labor.

Nazira Farah Sarkis, a Syrian politician and the State Minister for Environment Affairs.

Khawla Dunia, opposition activist and poet.

Îlham Ehmed, co-chairwoman of the Syrian Democratic Council.

Hêvî Îbrahîm, the prime minister of Afrin Canton.

Ulfat Idilbi, best-selling Arabic-language novelist.

Bouthaina Shaaban, Bashar al-Assad's political adviser and previous Minister of Expatriates

Hediya Yousef, co-chairwoman of the executive committee of the Federation of Northern Syria – Rojava.