Nawal El Saadawi, A Feminist Ahead of Her Time

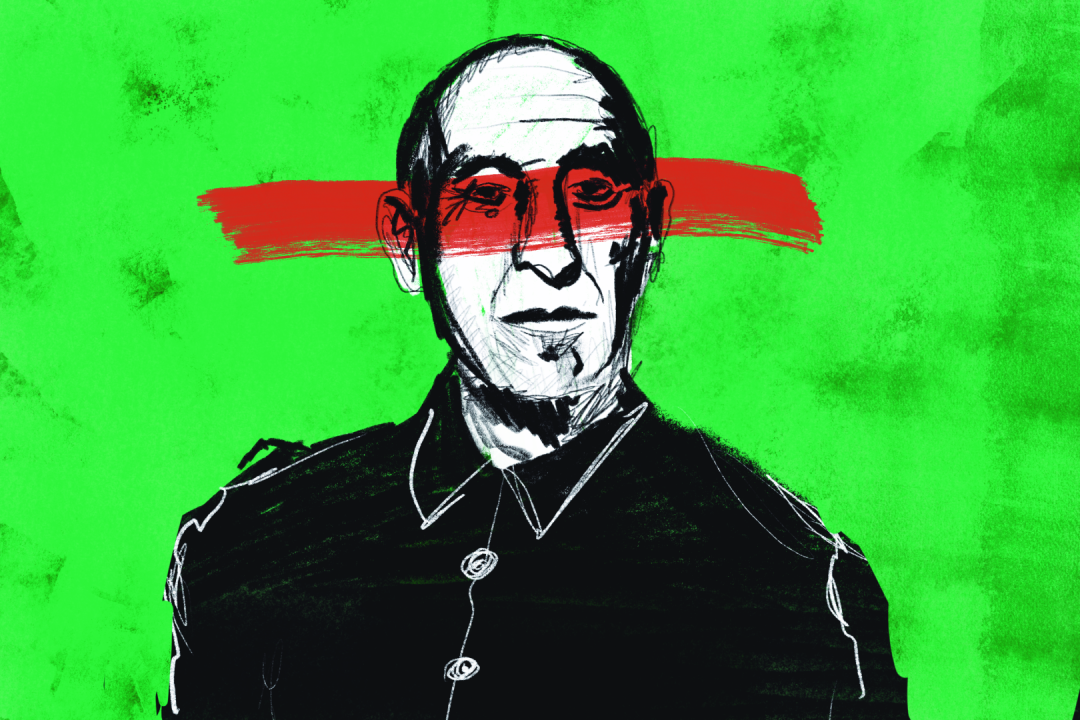

By: Perikhan Ismail Abdullah"They said, 'You are a savage and a dangerous woman.'

"I am speaking the truth. And the truth is savage and dangerous."

So wrote Nawal El Saadawi, who died at the age of 89, according to Egyptian media reports.

Nawal El Saadawi was the second of nine children born in a town outside of Cairo in 1931. Her mother was from a wealthy family, while her father was a government official. She grew up at a critical juncture in history, witnessed movements that advocated for girls' education pioneered by activists of an earlier generation. The famous advocate for women's education,“Nabawyya Mousa”, actually founded the school she attended.

El Saadawi was encouraged to go to the British School by one of her parents who valued education as a means for achieving social mobility. She was offered a scholarship to study medicine at the University of Cairo because of her scholastic ability, which also helped her avoid an early marriage.

In 1955, El Saadawi received her medical degree from Cairo University. She wed Ahmed Helmi in that year after meeting him as a medical school classmate. Mona Helmi, their daughter, was born. After two years, the marriage came to an end. Her second husband was a colleague, Rashad Bey but he showed a patriarchal dislike to her writings,which led to a divorce. In 1964 she married Hetata, who was a political prisoner and proved to be a much more durable companion and collaborator, and they had a son, Araf.

Over 50 publications, many of them novels, were published by El Saadawi throughout her lifetime. El Saadawi was detained in prison for three months at the Qanatir Women's prison in September 1981 as part of a roundup of dissidents under President Anwar Sadat. Memoirs from the Women's Prison, published in 1983, is based on her personal experience in prison.

Nine years prior to her imprisonment at Qanatir, she had an encounter with a prisoner there that became the inspiration for her earlier work; Woman at Point Zero (1975), the first of her novels that sparked widespread controversy, tells the tale of Firdaus, an Egyptian woman born into poverty who survives genital mutilation and several abusive relationships before becoming a sex worker.

Female genital mutilation (FGM) was one among the early events El Saadawi chronicled with unsettling candor, beginning when she was six years old. In her book, The Hidden Face of Eve (1977), she wrote about going through the horrible procedure on the bathroom floor with her mother watching. El Saadawi believed patriarchy and gender inequality oppress Arab women. She believed that Arab feminism theory is also closely related to the patriarchal religious discussion. With the help of several feminist manifestos, she shot to stardom in the 1970s. The first one was Women and Sex (1971), in which she denounced abuse against women's bodies, such as genital cutting, defloration on wedding nights, and honor killings. Her medical background allowed her to make the case that gender disparities are not biological but rather the result of patriarchal practices, which can be addressed through legislation and education.

El Sadaawi believed that, “in a capitalist society, gender equality is impossible.” Her magazine which she founded was shortly shut down after publication, and she lost her job. However, favorable response from the general public on her writing inspired her to produce other polemics, such as The Female is the Origin (1974), Woman and Psychological Struggle (1976), Man and Sex (1976) and The Hidden Face of Eve (1977).

By merging feminism and pan-Arabism in the establishment of the Arab Women's Solidarity Association (AWSA) in 1981, El Saadawi gained recognition in the west and established herself as a leading voice for Arab women

El Saadawi decided to leave Egypt in January 1993, when her name showed on a fundamentalist death list in 1992, and she found it difficult to deal with the armed guard that the Egyptian government had assigned to protect her. In the following years, she divided her time between writing her memoirs, which were released in two volumes in English as A Daughter of Isis (1999) and Walking Through Fire (2002), as well as teaching dissidence and creativity at Duke University in North Carolina (2002).

El Saadawi spoke against gender injustices with the authority of a physician, the knowledge of an intellectual, and the emotion of a devastated woman by combining patient anecdotes, her biography, medical and social research, and her own experiences.She studied women's physical and psychological issues through her medical practice and made connections between oppressive social norms, patriarchal oppression, class oppression, and imperialist oppression. When asked by the BBC's Zeinab Badawi in 2018, if she should tone down her criticisms, she retorted, "I should be more aggressive, because the world is becoming more aggressive, and we need people to speak loudly against injustices." In 2020, Time magazine named her as one of the 100 most influential women of the twentieth century.